Diane Keaton’s family has confirmed that the Oscar-winning actor died of pneumonia on October 11 in California at the age of 79, ending days of speculation about the sudden loss of one of American cinema’s most distinctive voices and screen presences. In a statement shared with People, the family said they were “very grateful for the extraordinary messages of love and support they have received these past few days on behalf of their beloved Diane,” adding that she “passed away from pneumonia on October 11,” and noting that suggested tributes in her memory include donations to local food banks or animal shelters, reflecting causes she supported throughout her life. The confirmation was echoed by multiple outlets quoting the same family statement, with representatives declining to provide additional medical detail beyond the diagnosis.

Keaton’s death was announced by her family over the weekend without an immediate cause, prompting a wave of remembrances from collaborators and admirers while authorities completed routine notifications; by Thursday, the family’s statement specifying pneumonia brought the first authoritative medical detail into public view. People reported that her health had “declined very suddenly” in recent months, a development friends said she kept within a close circle, and a separate remembrance characterized her as “funny right up until the end,” a description that aligns with the public wit and self-possession that defined much of her career. Early tributes organized around her work and her idiosyncratic public persona—brisk, self-deprecating, sometimes deflecting—now sit alongside a clearer account of what ended her life.

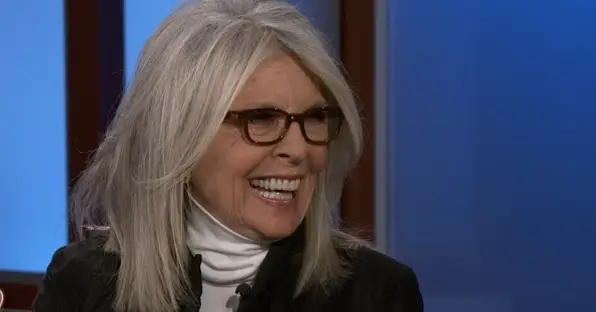

Born Diane Hall in Los Angeles on January 5, 1946, and raised partly in Santa Ana, she took her mother’s maiden name professionally and built a five-decade screen career that threaded major chapters of American film history, from the New Hollywood 1970s to the studio comedies of the 2000s. After stage work that included the original Broadway run of Hair and a Tony nomination for Play It Again, Sam, she became a fixture in Woody Allen’s films—most visibly in Annie Hall, for which she won the 1978 Academy Award for Best Actress—and expanded into a broader portfolio that encompassed The Godfather trilogy, Reds (for which she earned a second Oscar nomination), Marvin’s Room, The First Wives Club, The Family Stone and Something’s Gotta Give, the last cementing a late-career run as a romantic lead who carried humor and melancholy in equal measure. News accounts summarizing her legacy in the hours after her death reiterated those cornerstones while adding notes on her work as a director of music videos, a photographer and a memoirist with an eye for design and Los Angeles architecture.

Details released with the family statement underscored elements of Keaton’s private life long known to fans and colleagues. She never married, adopted two children—Dexter in 1996 and Duke in 2001—and spoke often, including in interviews revisited this week, about taking joy in motherhood later in life and about choosing independence over traditional milestones. People’s archives highlight her frankness about therapy, her distaste for plastic surgery and her habit of undermining the mythology that surrounded her image by playing with it rather than fleeing it. Those personal notes were recirculated this week alongside obituaries and appreciation pieces that placed her in a small class of performers whose name on a poster—paired with a hat silhouette, a high collar, a tailored coat—rendered a film instantly legible.